Ancient DNA Study Reveals Complex Interaction History Between Ancient Western Tibetans and External Populations

2024年7月23日Who’s Afraid of Genetic Ancestry?

I am a slash youth, a “omnivorous” scholar passionate about cutting-edge science!

A new article in Science magazine argues that the use of continental ancestry categories in scientific research needs to change.

The concept of ancestry is used in population genetics, archaeology, and genetic genealogy. With the push for more clinical genomics and personalized medicine, it is also becoming increasingly popular in health research.

In a recent policy forum held in the prestigious Science magazine, an interdisciplinary team of scholars from fields such as medicine, genetics, sociology, and bioethics questioned the use of genetic ancestry categories in scientific research.

But what exactly is genetic ancestry, and why does it matter how we use it in science?

What is Genetic Ancestry?

“Genetic ancestry” is not a synonym for plain old “ancestry.” Your ancestors, or genealogical ancestors, refer to your forebears—the people you descend from. These are your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and so on, tracing back through history.

However, your genome may contain only a small amount of information from some of those ancestors. Parents pass only 50% of their DNA to their children, and the DNA fragments from parents are shuffled and recombined in each sperm and egg cell in different ways.

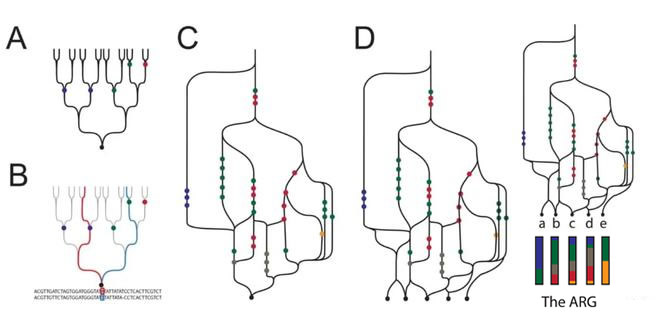

Therefore, to understand a person’s genetic ancestry, you need to look at the genome itself and trace how DNA fragments have been passed down over time. This can be represented using something called an Ancestral Recombination Graph (ARG)—which looks a bit like a family tree but specifically tracks the inheritance of DNA.

Research assistant Anna Lewis from Edmond J says, “We define it as the way each of us inherits different parts of our genome through our family tree.”

So far, so good. The main issue comes from how scientists and others choose to classify and label this kind of ancestry.

“You may notice that the definition doesn’t refer to any types of grouping.”

However, scientific research often classifies people into categories, with one system being particularly popular. A 2017 analysis of articles in Nature Genetics reported that since the 1990s, the use of continental ancestry labels, such as “African” and “European” ancestry, has significantly increased.

These labels might not be based on direct knowledge of an individual’s genetics but rather on their assumed or self-identified ancestry. For example, a white person might be classified into the “European ancestry” category without knowing if every ancestor who made meaningful contributions to that person’s DNA actually came from Europe.

The Long Shadow of Race Science

To understand what’s at stake here, it’s important to grasp the dark history of race and science—a vast topic in itself—and how it reverberates today in genetics and medicine.

In 1735, Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus—the father of modern scientific naming systems—classified humans into four colored “races”: “white” Europeans, “red” Americans, “yellow” Asians, and “black” Africans. Since then, Western science has struggled to move beyond similar classifications. Despite genetic data clearly showing that commonly understood human “races” do not correspond to distinctly identifiable genetic groups. Two people can belong to the same “race” and have very different DNA and ancestry.

Experts Say

Race needs to be understood as a social and political construct, not a biological one. Both Lewis and Cambridge University population geneticist Aylwyn Scally point out that in the early 20th century, people from Southern European countries like Italy and Greece were often excluded from the white category, and the concept of whiteness was a different race from Nordic people.

“Who is defined as what is highly context-dependent and often reflects which categories suit whoever is in power.”

“Race is a proxy for racism, which is an important thing. So in various studies, collecting race as a variable is very appropriate… but race is not a good proxy for any biology.”

Experts say that race needs to be understood as a social and political construct, not a biological one.

But we do need some way to talk about human genetic variation, even if race is not it. Queensland University statistical geneticist Loïc Yengo works on developing models to predict disease risk based on DNA. He says that currently, scientists’ and clinicians’ ability to make these predictions accurately is hampered because most available genetic data comes from people of European descent.

Since these data represent only a subset of our species’ genetic diversity, it means disease predictions may be less accurate for those who do not share the common DNA variants in that database.

Saving Genetic Ancestry?

In this context, genetic ancestry seems like a more scientific, less problematic, more comprehensive, and appealing way to talk about human variation.

But can genetic ancestry deliver on this promise? In their recent paper, Lewis and her colleagues argue that it cannot.

First, continental ancestry groupings do not accurately capture the breadth of human genetic diversity. People and their genomes do not neatly fit into continental “types.” Instead, genetically, we all exist on a spectrum of more or less relatedness.

This aligns with what we know about human population history, where large-scale migrations and continuous mixing between groups have been the norm. Depending on the timeframe considered, we all have multiple ancestors.

“As far as we know, there has been continuous gene flow, migration, and movement across the world and among populations throughout our history… so genetic ancestry reflects this complexity.”

Additionally, Lewis and her co-authors warn that uncritically using continental ancestry categories could perpetuate the same simplistic and harmful racial categories the field aims to avoid. If we simply replace “white” with “European ancestry,” “black” with “African ancestry,” “Asian” with “East Asian ancestry,” and so on, it’s hard to see how continental ancestry categories help.

“The danger is that we are just swapping one set of terms for another, we haven’t made any progress, and we end up with the same problems we have been trying to address.”

Stanford University sociologist Aliya Saperstein says, “The ongoing uncritical conflation of ‘race’ and genetic ancestry shapes how people interpret study results, then makes decisions about funding allocation, research priorities, and patient care based on that misinterpretation.”

“If the presence of racism and other ‘environmental factors’ is not properly accounted for in research—alongside genetic factors—then study results are at best unlikely to alleviate racial inequities, and at worst could exacerbate them.”

How Can Science Get Genetic Ancestry Right?

The Science article calls for researchers to implement “a more nuanced concept of ancestry”—one that more closely reflects the fine-grained realities of our genetic histories and relatedness and moves away from simple labels. But what would that actually look like?

Lewis says it depends on the research, but she gives an example of geneticists trying to find links between genetic variation and disease. These geneticists might worry that having people with different continental genetic ancestries in their studies would obscure the link between genes and disease, making their results less informative.

“Often, they end up only focusing on one ancestral group or dividing people into these broad groups and then analyzing them. We argue that many of these practices are entirely avoidable.”

The illustration explains the concept of the Ancestral Recombination Graph (ARG).

(A) A person (represented by a black circle) and their direct ancestors’ lineage; (B) Pathways of DNA inherited through the lineage at a single position in that person’s genome; (C) The person’s ARG, representing the pathways of DNA inheritance but not each ancestor; (D) ARGs combined from multiple individuals. Source: Mathieson and Scally (2020), What is an ancestor? PLoS Genetics 16(3). © 2020 Mathieson, Scally, reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution license.

Instead, scientists should turn to analytical techniques and tools that can handle genetic ancestry in continuous rather than absolute terms.

Scally and Yengo broadly agree that retaining more complexity is preferable—not only from an ethical standpoint but also from a scientific one.

As a statistically trained geneticist, Yengo says he is used to thinking in continuous measures—but many analytical tools in genetics don’t work this way by default.

“If we could have software that doesn’t require us to label people upfront, I think that would be a great starting point.”

“There will certainly be better ways to exclude categories for as long as possible.”

Given that genetic ancestry is so complex and hard to categorize accurately, why bother classifying people at all?

“Scally thinks often, we should try to avoid it as much as possible. There will certainly be better ways to exclude categories for as long as possible and use these complex structures for longer. This will require bigger, better tools, more computational resources, and similar things, but it’s entirely feasible.”

However, he is skeptical about whether categories can be completely abandoned.

“It will still reach a point where [scientists] want to try to present their results and talk about their findings. Without attaching some kind of label, that would be very difficult.”

But abandoning all ancestry categories isn’t what Lewis and her co-authors are really calling for. They want scientists to avoid using categories where possible and think more deeply and critically about what those categories describe—whether genetic or environmental differences, or both.

Hopes for the Future?

Saperstein points out that the new Science forum is not the first to raise similar issues.

“Unfortunately, even if most people theoretically agree with the argument, most genetic and biomedical researchers seem not to have put it into practice.”

“He believes the tide is finally turning, with genetic researchers finally questioning taken-for-granted approaches in their field. But

this isn’t the first paper to make this argument, and it won’t be the last.”

“I believe the tide is finally turning.”

Lewis is more optimistic, citing her experience guiding an interdisciplinary group that included geneticists, bioethicists, sociologists, and anthropologists to reach a consensus on the new paper.

“The field does have some ways to move beyond them, but Lewis believes people don’t fully understand the moral imperatives of making these changes… we need to do more work, we need to change a lot of minds.” Meanwhile, the takeaway message for all of us is to remember the complexities that genetic ancestry categories simplify and always ask ourselves what they truly represent.