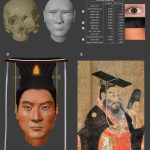

Ancient DNA reveals intriguing details about a sixth century Chinese emperor

2024年4月2日

Comparison between ancestral halls and churches from the perspective of innovative social governance

2024年4月16日An overview of research on clan issues in rural China since the 1990s

Author:温锐 蒋国河 Source From:中国乡村发现

Section 1: Discussion on the Reasons Behind the Revival of Clans in Contemporary Times

After the reform, the rapid revival of rural clans, previously deemed as feudal dregs, has become a topic of great interest among scholars studying rural areas and peasants. Notable among these scholars are Wang Huning, Qian Hang, and Wang Mingming.

Mr. Wang Huning focuses on the economic factors and administrative systems to explore the reasons for the revival of rural clans. He believes that economic factors are the root cause: “Over the long years, no significant force has emerged to challenge the family culture, primarily due to the lack of strong material production forces;”[1](p6) Moreover, he points out that the weakening and withdrawal of administrative control have allowed kinship and familial consciousness and power to thrive, as the seasonal nature of agricultural production makes necessary production cooperation indispensable. However, the weakening of collective economic management has led to families naturally becoming the primary agents of such cooperation, thus “leading to the rise of family power.”[1](p64).

Scholar Qian Hang explains the revival of rural clans primarily from a cultural perspective. He argues that the reason for the clan’s persistence is not due to its external functions but rather signifies a cultural root shared by clan members. This root forms the source of their existential value because, in the current social structure, the clan is almost the only form of autonomy that truly integrates with their real lives. It not only satisfies people’s need for a sense of history and belonging but also serves as a mediator linking tradition with reality, fulfilling people’s sense of morality and responsibility in real life.[2](p22-29).

Mr. Wang Mingming and Mr. Zhu Hong prefer to analyze the reasons for the revival of clans from a functional sociological perspective. Wang Mingming believes that the revival of clan communities is due to clans meeting certain needs in public welfare, social welfare, and spiritual aspects. He notes that post-1979 reforms introduced new challenges in cooperation and mutual aid: economic reforms led to the revival of household economies and partly reduced the government’s “public” power, especially as direct government intervention in economic cooperation and rural public welfare was abolished. Not only did production become a private household affair, but public welfare and social mutual aid also turned into civil matters. This situation provided a “free space” for the restoration of traditional social mutual aid systems.[3](p63-64). Zhu Hong highlights the economic effects of the revival of clans. He observes that returning overseas Chinese seeking their roots can bring significant economic benefits, “which is why local governments often tacitly or even supportively approach village clan activities, aiming to attract business and promote local economic development”; moreover, clan power plays a crucial role in protecting peasants’ economic interests and safeguarding their legitimate rights, for example, when higher levels arbitrarily appoint village officials or when local departments impose arbitrary fees, increasing peasants’ burdens, clans have some power to resist, whereas individuals and families not affiliated with a clan are powerless to contest such actions.”[4].

In addition, scholars like Mai Wenlan and Yu Hong have explored how negative psychological factors and a lack of spiritual life among peasants contribute to the revival of rural clan activities. Regarding the deficiencies in peasant spiritual life, Mai Wenlan believes that rural youth lack spiritual and cultural activities, making it easier for clan power, using clan culture, to gather clan members; the clan color of rural community culture is increasingly strong, as seen in the use of rituals, clan plays, and weddings and funerals, where the dregs of clan culture impact the construction of rural spiritual civilization.[5]. Yu Hong suggests that negative psychological factors in peasants also contribute to the revival of rural clan power. She points out that traditional clan culture, clan consciousness, and clan sentiments contain the Chinese peasants’ need for an “ontological” sense of human identification and belonging, providing psychological satisfaction that keeps clan members emotionally connected to their homeland, even from afar. The root-seeking fervor since the opening-up reforms not only comforts their feelings of displacement but also relieves emotional debts, while various regions promote this clan sentiment to boost economic construction.[6].

Overall, from the current research, scholars have delved into the political structure, economic system, social function, cultural tradition, and psychological aspects to explore the reasons for the revival of clans, showing that these reasons are not one-dimensional but likely multidimensional, resulting from a combination of factors. The differences among scholars mainly arise from different perspectives: some view this issue from a positive angle, while others interpret it negatively; there is still a lack of comprehensive research based on these aspects. Therefore, further systematic and in-depth exploration is needed to understand the fundamental reasons (or main reasons) for the revival of clans. Although most researchers agree that the general revival of rural clans after the reforms is not a coincidence and must have deep-rooted reasons and rational elements, they also recognize that deeply ingrained clan concepts, cohabitation based on kinship, and underdeveloped commodity economies are also major factors in the cultural revival of clans post-reform. Clearly, scholars have not adequately recognized the fact that clan organizations and activities are generally reviving in the economically most vibrant southeastern areas of China, thus failing to reflect on the long-held academic view that the so-called “small peasant economy” hinders the development of the commodity economy, nor have they answered the relationship between clan organizations and the development of the commodity economy. As for some scholars who view the revival of clans as a revival of feudal dregs or a negative psychological factor in peasants, their approach appears overly simplistic and harsh. It is particularly important to note that when researching the reasons for the revival of clans, scholars rarely start from the political needs of peasants. It is well known that peasants, like workers, businessmen, intellectuals, and government officials, belong to different social interest groups; peasants are not only a large social interest group but also a vulnerable group among social strata. Faced with the establishment of a market system, the scattered peasant groups urgently need social organizations that represent their interests, but our society uniquely denies nine hundred million peasants the permission to have legitimate political social organizations. In fact, the absence of political social organizations does not mean that peasants lack their political demands; thus, in some rural areas with developed traditional clan cultures, clans become a valuable traditional organizational resource for peasants to utilize as a natural and cost-effective form of self-organization in the current social political landscape. Therefore, how to modernize the organization of numerous and dispersed Chinese peasants, the academic research on rural clan issues should contribute wisdom to the construction of our country’s political civilization.

Section 2: Research on the Transition of Rural Clans from Tradition to Modernity

Following the discussion on the reasons for the revival of rural clans is the question of what changes or transformations have occurred in rural clans during the transition from tradition to modernity. It must be said that scholars have made considerable breakthroughs in this area of research.

Wang Huning and other scholars have compared the characteristics of traditional and modern clans on multiple aspects and revealed the trends of contemporary clan changes. Wang Huning first proposes eight basic qualities of traditional family culture: kinship, cohabitation, hierarchy, ritualism, agrarianism, self-sufficiency, closedness, and stability [1](p29). After comparing contemporary family culture with these qualities, he believes that the foundations of village family culture have undergone the following transformations: (1) Kinship-based interpersonal relationships still exist, but no longer form the formal basis for social status; (2) The significance of geographical relationships is diminished, and mobility has increased; (3) Traditional rituals have been relegated to a secondary position, and legal factors have risen in rural life; (5) The singular mode of agriculture has been broken; (6) The family group’s social needs have increased; (7) The closedness of the family has been broken; (8) Long-term stability has also changed; (9) The social system force overwhelms the clan community, and social order dominates in rural areas; (10) The social system is now the main executor of village functions, while the village family still performs certain functions, but is no longer the main function [1](p212-213). Wang Huning also analyzed the contemporary Chinese rural traditional authority structure—the clan elders. He distinguishes four types of clan elders based on their status: one is the honorary type: enjoying a certain status and prestige, having a say in some clan affairs; two is the arbitration type: enjoying a certain status and authority, possessing some power, playing a regulatory role in the village family; three is the decision-making type: they have substantial actual power, enjoy higher status, able to make decisions on major issues within the clan; four is the managerial type: they possess most of the actual power, holding the highest status. Among these, the arbitration model is most common, the decision-making model is relatively common, and the managerial type of clan elders is decreasing. He believes that although clan elders still exist in contemporary clans, they have undergone changes; this change reflects the direction of social evolution. Through comparison, Wang Huning believes that village family culture has undergone decisive changes under the impact of historical-social-cultural transformations, its dissolution is a historical trend, and restoration is a specific phenomenon [1](p279).

Qian Hang, after comparing traditional clans with those undergoing modern transformation, believes that the recently restored clan organizations, both in structure and function, should not be seen as mere repetitions or replicas of the old clan form, but rather as a stage product in the transformation process of traditional clans. Firstly, the structure of clans in transformation differs significantly from traditional clans, with the former mostly lacking a definitive clan leader and instead having one or a few “clan affairs conveners,” which mainly refers to a temporary functional work team formed for conducting a specific affair; traditional clans differ, especially in clans since the Song Dynasty, where clan leaders not only had definitive identities but also were numerous. Secondly, clans in transformation exhibit the following organizational characteristics: one, diversity of forms; two, no formal clan names; three, instability, many clans at least formally have temporary characteristics; four, direct relationships between ordinary members and clan leadership [2](p57-58). He also reviewed the 1998 revised genealogy of the Mei Geng Wang clan and compared it with an old genealogy, pointing out that the “Prefaces” of these two genealogies reflect significant differences in the spirit of the times, clearly showing the changes in clans with the passage of time [2](p112).

Wang Mingming’s research on the changes in rural clans is approached from a social anthropology perspective. He divides the changes in the family system since the Ming and Qing dynasties into three periods: the village clan period, the Baojia period, and the New Village Politics period. During the village clan period, local power had a great deal of autonomy [3](p41-42); the implementation of the Baojia Law during the Republic of China “broke the pattern of village politics based on village clans.” However, the author points out that the establishment of the Baojia Law did not lead to the extinction of the family system, but merely meant that it was replaced by a new administrative and power structure as a form of village politics. The organization, regional networks, economic functions, and rituals of the family were relatively preserved [3](p43-44). Since 1949, although the collectivization system severely suppressed and cracked down on clan power, even during the Cultural Revolution, intense familial and factional conflicts still occurred within collectives [3](p46). Regarding contemporary clans, Wang Mingming believes that although today’s clan organizations are not formal power organizations and appear superficially as temporary institutions distinct from so-called power, they still display certain functions of civilian power through the construction of public temples and rituals. The authority of clan leaders comes from their own prestige and the trust and support of villagers, seen as spokespersons for local interests. What they possess is a kind of “educational power” and “consent power,” rather than coercive power [3](p79-82).

Chengkang Fei, after comparing the new and old clan family rules, pointed out the characteristics of changes in family rules over time. He compared four aspects: one, the scope of norms is different: the relationships adjusted by the new clan rules have greatly decreased, and the scope of their norms is only a small part of the traditional family rules; because these rebuilt clans no longer have clan fields, ancestral graves, clan schools, charitable estates, and some have not yet rebuilt clan halls or just started to revise clan genealogies, so these newly established clan rules do not contain content related to clan fields, clan properties, clan schools, charitable estates, or even clan halls. Two, different concepts are reflected: due to significant changes in the times, the impact of old ritual education on society has greatly declined, and the thoughts, views, upbringing, and social status of those who establish new clan rules differ from those of the old times. Three, different behaviors are punished: as societal concepts have significantly changed, the behaviors punished by new clan rules have also changed accordingly; many of the behaviors punished by old family rules are no longer punishable by new clan rules. Four, different methods of punishment: the punishment methods that can be retained in new clan rules are generally only a few, such as cutting off from the genealogy, not allowing entry into the clan hall, not allowing burial in the ancestral grave, and fines, mainly of a spiritual nature. Of course, he also points out that not all clans or all practices of clans conform to the spirit of the times, such as the stipulations on fines found in some clan rules [7](p228-233).

Wang Shuobai and Chen Yixin discussed the changes in clans after researching three clan villages in Anhui. They believe that the “citizenization” process began after the reform, as rural clans were not shattered by the revolutionary regime during the early Republic period, but encountered historical disintegration during the reform. They note that under the collectivization policies based on villages in cooperatives and people’s communes, traditional collective clans continued due to organizational isomorphism with the new system and were strengthened when peasants sought protection resources within themselves in the face of disasters. However, the reform granted peasants economic autonomy, village elections, urban labor, and other modern rights, starting their “citizenization” process, causing clans to lose their successors among a large number of young people, and the cherished kinship relationships in clans being replaced by national and civic social contracts [8].

From the current research results, researchers generally agree that compared to traditional clans, contemporary rural clans have undergone significant changes or transformations and are gradually disappearing in social development; differences exist only in the degree of these changes and the interpretation of their significance. On this matter, we believe that researching the changes in clans essentially involves studying the changes in peasant consciousness and rural society. Therefore, two aspects should be given attention by researchers:

1. To make an accurate assessment of the degree of change in current rural clans, researchers should not be satisfied with the “typical study” approach. The acquisition of research materials should span time and space, and only then can the research results claim a certain universality. However, a lack of a large number of empirical case studies, especially a lack of medium- and long-term historical comparative studies, is a common shortcoming in current research on rural clan issues. In fact, contemporary Chinese clan forms are extremely complex, with significant differences in clan concepts and clan power between northern and southern regions. Diachronic research should be combined with synchronic research, and only through horizontal and vertical comparisons can the real face of rural clan changes be more objectively and accurately reflected.

2. Interpretation of the significance of changes. Specifically, how to understand the social significance of these changes and the trends or development tendencies these changes will lead to, which are directly influenced by the researcher’s value stance, especially their view of social development. Looking at the same rural clan issue from the perspective of political science differs from the perspectives of social anthropology or historical anthropology, as researchers from these different disciplines have significant differences in their views on social development. Indeed, the issue of rural clans is essentially about the kinship groups of human society; their social changes and the direction of social development they reflect are essentially about whether the peasant group can keep up with the times. Thus, whether the changes in clans will lead to their complete disappearance or the disappearance of certain aspects is a matter that deserves further consideration and should not be hastily concluded. For example, a citizenized society is a common feature of human social evolution, but does this necessarily lead to the complete disappearance of community traditions? As long as urban-rural differences exist, rural-specific cultures will not completely vanish; China’s citizenization process may have started or made significant progress, but this is a relatively long process; merely discussing the disintegration of rural clans based on partial surveys and analyses of a few villages is still premature.

Section III: The Role of Clans in Modern Rural Democratic Politics

The role that contemporary rural clans play in the increasingly advanced grassroots democratic politics is a hot topic of interest to scholars, especially since the implementation of “open elections” in village elections, which has heightened academic attention and deep thought due to the active participation of Chinese peasants in voting.

Scholars like Xiao Tangbiao, Lan Yunzhi, Wu Sihong, Yuan Zhengmin, and Lv Hongping believe that rural clan organizations and their activities mainly have a negative and passive impact on village self-governance and elections. Xiao Tangbiao argues that the positive functions of clans have irreversibly declined and that because clans operate on the principle of strength in inter-clan relationships, the consequences are negative and severe. Lan Yunzhi observes that the high frequency of current clan activities, whether overt or covert, confronts and provokes village self-governance activities, preventing them from functioning normally; major clans often dominate, influencing the creation of village committee members through “legal means” of larger numbers and votes during elections. In such clan struggles, a village committee’s self-governance is non-existent. Wu Sihong notes that the rise of clans and dark money forces has alienated self-governance power; during the formal implementation of the “Village Organization Law,” they often use kinship ties or form interest groups to control village elections unfairly to seize self-governance power. Yuan Zhengmin points out that the negative impact of clan power on village self-governance is multifaceted, almost infiltrating every aspect of village self-governance work. The main impacts include affecting the fairness of election work, disrupting the normal conduct of elections, and impacting the quality of village leaders and the stability of the leadership team. He believes that the size of clan power and the quality of the peasants are directly related; where peasants have higher quality, the impact of clan power on village self-governance is not significant, but where peasant quality is lower, clan power issues are more pronounced. Lv Hongping believes that family forces interfere with village governance and elections; in some villages, many families hold clan meetings, organize alliances, and canvass votes to disrupt the normal election process, affecting the fairness of elections.

Zhu Kangdui, Tong Zhihui, and He Xuefeng hold a positive view on the relationship between clans and village self-governance and elections. Scholars like Zhu Kangdui, Huang Weitang, and Ren Xiao, after extensive empirical research and analysis in rural areas, have unique insights into the issue of major clans overpowering smaller ones in village self-governance elections. They note that while a major clan may dominate all seats in an election, the elected village committee will struggle to function without the participation and cooperation of other clans and family groups, as seen in their study of Jinjiayang Village in Wenzhou, Zhejiang. To enhance the representativeness of the village committee, they might motivate individual candidates from their families to step down to make room for members of smaller clans. The authors also mention that clan preferences among villagers during elections are inevitable, but if elections are conducted fairly, openly, and justly, the outcomes often reach a certain balance. Tong Zhihui has studied the importance of clans as a form of village social connection or community of interest for elite mobilization in elections, clearly denying that clan interests hinder the fairness of village self-governance. He argues that factors of family and faction used in elite mobilization do not necessarily rely on highly institutionalized family organizations or factional groups; elite mobilization often has a strong personal character, with family and faction merely serving as means of mobilization. In post-election village governance, family and factional interests are not the sole basis for governance; instead, the family interests and factional consciousness constructed during elections often dissolve naturally and are no longer mentioned. He Xuefeng and Tong Zhihui’s joint research highlights the importance of clans as a traditional type of social connection for village self-governance. They argue that traditional social organizations like clans can serve as indicators of villagers’ capacity for action, effectively seizing opportunities provided by marketization in addressing agricultural difficulties and rural development needs, which in turn intensifies economic and social differentiation in rural areas and develops modern social connection capabilities in villages.

Some scholars argue that the role of clans must be analyzed based on specific contexts. Guo Zhenglin believes that there are four different types of interaction structures between village committees and families: in villages where the party branch is highly respected and the village committee is powerful, families generally form a healthy interactive relationship with the village committees, enhancing the community spirit of cooperation. In villages where the party branch is strong but the village committee is weak, the party branch controls the village committee and also the social capital of families. In villages where the village committee is strong but the party branch is weak, since the party branch cannot extract social resources from family relations and the village committee holds such social capital, it plays a political role in advancing the interests of village families. The last scenario is where both the party branch and the village committee are weak, which might result in either pure family rule or a comprehensive failure of all three entities.

Other scholars believe the influence of clan interests on village elections is extremely limited. Hu Rong points out that although traditional family concepts influence the identification between voters and candidates and family factors play some role in elections in smaller administrative villages or village groups, geographic rather than clan relationships become the main factor influencing villagers’ choices of candidates. In the ranking of voting preferences, geographic factors clearly outweigh family factors.

It can be said that in the overall research on rural clan issues, the relationship between clans and village self-governance is a deeply explored issue with significant breakthroughs, especially the results provided by scholars like Tong Zhihui, He Xuefeng, and Zhu Kangdui, which have brought the study of village self-governance into the depths of political ecology using political science’s checks and balances theory, providing new insights for the construction of a politically civilized rural China with distinctive characteristics. Naturally, it is precisely because of some scholars’ in-depth research and new breakthroughs that there are significant divisions in the academic community on this issue, with the core disagreement being whether the activities of rural clan organizations are beneficial to village self-governance and elections. To reach more consensus among scholars on this issue, in addition to valuing different research perspectives, it is also important to clarify two key questions:

First, it is necessary to clarify who the interest subjects of rural clans are. Rural clans are interest group organizations, with different clans having different interests, yet the main body or main members of each clan are peasants. Therefore, the interest subjects of rural clans are peasants, and different clans merely represent different communities of peasant groups. It should be clarified that the vast majority of peasants are the great initiators, supporters, and active participants of China’s reform and opening-up, and challengers of the traditional collective system. Clarifying this helps us break away from the long-established mindset of feudalizing peasant organizations or backwardizing peasant groups, and achieve a shift in thinking about peasants and rural clans.

Second, it is necessary to clarify the legitimacy or compatibility of this subject’s interest demands, i.e., whether they conform to the spirit of village self-governance. Once it is clear that peasants are the interest subjects of rural clans in the new era, according to the four “democratic” spirits of village self-governance (as stipulated in Article 2 of the Village Group Law officially promulgated in 1998: “The Village Committee is a grassroots mass self-governing organization for self-management, self-education, and self-service by villagers, implementing democratic elections, democratic decision-making, democratic management, and democratic supervision”), the legitimacy or compatibility of the broad participation of peasants in village self-governance elections through legal channels is also clear. Of course, this legitimacy may contradict our traditional or habitual thinking, which involves adjusting the perspective and scope of issues discussed later in the text.

Section IV: The Relationship between Clans and Socio-Economic Issues

The relationship between contemporary clans and socio-economic issues is also a major concern in academia. How to accurately understand the influence of clans in contemporary socio-economic contexts not only involves accurately grasping the so-called issue of family businesses in reality but is also a crucial indicator for understanding contemporary clans. Many historians have conducted research on the relationship between traditional clans and socio-economic issues, achieving fruitful results. These studies are mainly focused on two aspects: (1) Studies on the economic functions of clan properties such as clan fields, educational fields, charitable estates, and charitable donations since the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, such as Chen Zhiping’s “Family Society and Culture in Fujian over the Past 500 Years” (published by Shanghai Sanlian Bookstore in May 1991), Kong Yongsong and Li Xiaoping’s “Hakka Clan Society” (published by Fujian Education Press in October 1995), Chang Jianhua’s “Clan System” (published by Shanghai People’s Publishing House in 1998), Chen Keyun’s “Clan Properties in Ming and Qing Huizhou” (seen in “Qing History Forum”, published by Liaoning Ancient Books Publishing House in 1992), Ye Xian’en and Tan Dihua’s “On the Clan Fields of the Pearl River Delta” (from “Studies on the Socio-Economic Form of Ming and Qing Guangdong”, published by Guangdong People’s Publishing House in 1985), and more. (2) Research on the relationship between clan culture aspects such as rituals, kinship, ethics, and commodity economy. This includes Japanese scholar Usui Sachiko’s “Hu Merchants and Their Networks” (in “Anhui Historical Studies”, Issue 4 of 1991), Tang Lixing’s “Dual Variations of Merchants and Culture: Historical Examination of Hu Merchants and Clan Society” (published by Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press in 1997), and articles published in “Southeast Academic” Issue 6 of 2001 hosted by Fujian Academy of Social Sciences, including Wang Rigen’s “Development of Family Culture in Southeast China during Ming and Qing Dynasties and Its Interaction with Economic Development”, Zhang Xianqing and Zhan Shichuang’s “Regional Integration of Traditional Ritual Systems and Folk Values: The Inner Content of Southeast Folk Spirit and Its Relationship with Economic Development”, and Chen Jinguo’s “Rational Drive and Compatibility of Righteousness and Profit: A Brief Discussion on Song and Ming Neo-Confucianism and Socio-Economic Changes in Southeast Family Society”. Research on traditional clans and socio-economics is not only plentiful but also largely consistent in many aspects, such as the collective sense of clans and their high cohesion being conducive to mutual aid and cooperation in economic activities; certain spiritual connotations and value concepts in clan culture positively affecting rural economic and social changes, even promoting the development of modern urban and rural industrial and commercial activities. In fact, these excellent qualities and cores of clans are precisely why they still maintain vitality today. This point is also widely reflected in the research on the reasons for the contemporary revival of clans. Contemporary clans have emerged alongside rural reform and the development of China’s market economy, and they have a closer relationship with the socio-economic development of contemporary rural society. However, contemporary clans have significant differences from traditional clans in structure, function, and ethics, such as the non-existence of clan properties and clan fields, and the socio-economic basis for the existence of clans has also changed significantly. At the same time, due to the input of Western economic and sociological theories and research methods, there has been a significant change in the academic thinking structure of scholars, and the focus of academic research has shifted, with research perspectives showing a diversified development trend. Some scholars have also explored the relationship between contemporary clans and modern socio-economic development from the perspectives of clan structure and demography, among which the focus on and research on family business systems have become hot topics in the study of rural clan issues.

Since the 1980s, family businesses or township enterprises mainly managed by families that flourished in the Jiangsu and Zhejiang regions have attracted wide attention from scholars, and research on family business systems has thus prospered. How to evaluate and position family businesses? How to view the impact of family culture on businesses? How to understand the historical fate of family businesses in the establishment and standardization of China’s modern enterprise system? These have become hot topics in academic research.

In China, family businesses have long been criticized by the social elite, considered to be inefficient and doomed, and bound to be replaced by so-called modern enterprise systems; recently, scholars like Yang Tonghe and Li Canrong still believe that while family-based operations played a significant role at the beginning of the entrepreneurship of private enterprises, when the business develops to a certain stage, the family system becomes an obstacle to business development, causing stagnation. The author proposes three reasons: first, family-based management often leads to decision-making errors, with the most obvious being “patriarchal management”; second, family-based management hinders corporate innovation; third, family-based management affects internal unity within the enterprise, hindering the construction of corporate culture, thereby burying hidden dangers for business development. Tang Meifang also points out that in addition to high trust and strong cohesion, the exclusivity in Chinese family business culture is apparent; this exclusivity is detrimental to its further development in the pursuit of strength, size, and speed in the second entrepreneurship after joining the WTO, and in standing out in competitive survival of the fittest.

However, scholars like Chu Xiaoping, Pan Bisheng, and Chen Gonglin have questioned this. Chu Xiaoping, a professor at Shantou University, conducted a dialectical analysis of the efficiency of family businesses, proposing that the efficiency of family businesses requires specific analysis, with the standard being the essential requirements of the market economy, i.e., the continuous expansion of human cooperation order. The author believes that under specific conditions, the loyalty and trust relationships among family members, as a resource for saving transaction costs, enter into the business, and family ethical constraints simplify the enterprise’s monitoring and incentive mechanisms, making family businesses efficient economic organizations. However, when family businesses are in market competition, their internal limited resources and the low management capability of family or clan members lead to high internal transaction costs compared to non-family business competitors, resulting in low competitiveness; then, family businesses are unreasonable and inefficient. Pan Bisheng, after investigating township enterprises in Jiangsu that implemented family management after restructuring, further believes that this type of family management is generally a successful reform, adapting to the level of productive forces development. This organizational form fully utilizes the dual forces of kinship and interest relations, as well as the regional specificity of community economy, making it an effective carrier for accepting and promoting industrial civilization. The author optimistically predicts that community enterprises in China will mainly be family businesses in the future. Fuzhou University professor Chen Gonglin, after comparative analysis, believes that an enterprise system is always connected to the political, economic, and cultural environment of its society; under certain social backgrounds, family businesses definitely have more advantages than non-family businesses, otherwise they would not be a widely chosen enterprise system. He uses family businesses in the United States and Japan as examples, analyzing the advantages of family businesses after discussing them: first, family businesses have a property rights system that can make the best decisions because the capital owners of family businesses are the decision-makers, and this property rights system with skin-in-the-game is an important guarantee for reducing corporate decision-making errors; second, the property rights system of family businesses is conducive to reducing costs; third, the vitality generated by the common struggle spirit of interest sharing and risk sharing created by family business kinship relationships is strong, and the positions of decision-makers in family businesses are determined more by kinship relations, so in more cases, family businesses exhibit a spirit of unity, mutual assistance, and collective endeavor. The author also analyzed why many countries and regions in Asia are predominantly family businesses. He pointed out that in the context of underdeveloped markets in Asia, family businesses still have their irreplaceable advantages, able to overcome the deficiencies of the credit environment. On the other hand, emphasizing interpersonal relationships or human relations is also a kind of investment, or a kind of social capital. The investment in this social capital yields greater returns when market mechanisms and public goods provision mechanisms are less perfect, i.e., it has greater cost-effectiveness. We believe this should be the same for the above two types of businesses.

Section V: Macroscopic Propositions—Reflections on the Issue of Clans and Modernization

The academic community’s sustained interest in researching clan issues is actually derived from a value judgment and care for rural clans, a traditional aspect of Chinese culture, i.e., whether clans are conducive to China’s modernization or whether clans can integrate with the increasingly modernized Chinese society. It also concerns what role clans should or can play in the modernization process of Chinese rural society, how clans will fare in modern society, and more. As Mr. Wang Huning states, these are issues concerning “the development of Chinese society” [1] (p7), not only possessing high academic value but also having strong practical and policy significance. Research on the relationship between clans (including traditional clans) and contemporary socio-economic, political, and cultural development is actually a concrete demonstration and expression of care for the historical fate of traditional culture.

Regarding the issue of clans and modernization, there are two main views in direct macroscopic discussion. One view believes that clans, overall, are not conducive to advancing China’s modernization but are obstacles to the socio-economic and political development of Chinese society. These scholars generally have a negative attitude towards clans, although a considerable part of them also acknowledge that clans contain some positive elements and even have their rationality. Wang Huning’s view largely belongs to this category. He believes that the conceptual system of village family culture is often detrimental to social integration, the operation of social systems, the implementation of social legal norms, the formation of civic culture, and ultimately to China’s modernization [1] (p288). However, as mentioned earlier, he also acknowledges that village family culture, regardless of its historical and contemporary manifestations, always contains certain positive factors [1] (p288). He Qinglian further believes that the revival of clan organizations in Chinese rural areas, no matter from which perspective, is a cultural recession that will inevitably lead to severe social conflicts. Its development and growth mean that China’s modernization still has a long and winding road ahead [29]. Xie Weiyang’s view is very representative in maintaining a negative attitude. He believes that the Chinese clan system fundamentally does not meet the demands of modernization. The author proposes that the most essential characteristic of the Chinese clan system is that some people, regarded as clan leaders, control, manage, and dominate so-called “clan members” based on kinship reasons, including handling personal matters; the reason modern society gradually cancels the legal status of traditional clans is largely because the concept of clan management as an entity is contradictory to the principle of universal participation of all citizens. He further believes that ultimately escaping the private law control of clans is a necessary condition for peasants to achieve comprehensive development in modern society; although it is not necessary to deny the positive cultural and community life significance reflected in current clan activities, this is not essential, because the same cultural and community functions can be achieved in rural life without clans, and perhaps more rationally [30]. Lv Hongping believes that clan culture hinders the development of modernization in China from political, economic, and cultural aspects: firstly, clan organizations hinder the functioning of grassroots organizations in rural areas; secondly, the closed nature of clans restricts the construction of market economy systems, affecting the formation of modern economic structures. The author believes that peasants rarely value transactional value, and this value concept of valuing relationships and righteousness but disregarding benefits severely binds people’s market economy consciousness, affecting the transfer of rural labor and economic restructuring. It also breeds conservative ideas and dependency thinking, suppressing innovative spirit and self-awareness. Lastly, clan culture is also contrary to modern culture, constituting a restrictive factor in modernization thinking [13] (p314).

Qian Hang, Yang Ping, Qin Hui, Huang Shichu, Lu Xueyi, and other scholars hold views contrary to the above analysis. Qian Hang believes that due to the inherent reasons of Han Chinese clans that originate from kinship and transcend kinship, the reconstruction and transformation of contemporary Chinese rural clans obviously cannot be equated with the evolutionary rules of general kinship groups, and their fate and prospects must also differ. This can prove that under certain conditions, kinship factors, after proper supplementation and restriction, can completely form a complex adaptation relationship with the civilized life of modernization. However, he also believes that rural clans are best regarded as a kind of “club-style” association among rural individuals of the same surname, limiting clan activities within the community and aiming at self-help among relatives and promoting public welfare projects, without advocating clan interference in local grassroots political public affairs [31], which essentially means not allowing peasants greater autonomy. Yang Ping points out that family organizations play an extremely important role in rural politics, economics, culture, religion, etc., possessing a rather broad cooperation space with the Chinese state authority, and are not in an entirely opposite state to the main current of modernization. However, the author also notes that family organizations are a double-edged sword; inter-clan conflicts represented by them, as well as widespread dissatisfaction caused by improper government handling, could become a destructive force in the revival of family organizations [32]. Qin Hui believes that the development of clans reflects the promotion of individual development and modernization (the process of individualization) under specific historical conditions and development stages of “small communities,” therefore, the existence of kinship organizations in modern society is entirely conceivable [33] (p295-296). Huang Shichu believes that clans have high adaptability and flexibility, and clans can completely achieve modernization; in developed countries in Europe and America and emerging industrial countries and regions like Taiwan and Singapore, there are many clan organizations similar to traditional clans; their principles for absorbing members also have high flexibility, such as allowing members with honorary kinship to join clans, even including sons-in-law and nephews among clan members; the management system of clans is also quite flexible, ranging from kinship systems to chieftain systems to modern distinctive clan member congresses, and management by councils and supervisory boards elected by congresses replacing the authority of chieftains. The author also discusses the inevitability of clan modernization. The reasons are: the difficulty in changing the living mode of living together in clans; eternal kinship affection; risks and pressures brought by market competition requiring unity and mutual assistance for joint competition; political environment still providing living space, etc. [25]. Renowned sociologist and peasant scholar Lu Xueyi points out that judging village family culture by the linear standards of modernization inevitably overemphasizes its negative effects; in the process of modernization and post-modern society, village family culture will play an important role for a long time [34] (p15).

The research by the above experts and scholars has formed a multi-disciplinary, multi-angle participation in the research attack on rural clans, continuously advancing, deepening step by step, and breaking through continuously. This not only has taught the writer a lot and been greatly inspiring but is also changing many unquestionable mindsets that we have formed over nearly a century. Our feeling is: rural clans represent a grassroots social organizational force, and this organization is also a main carrier of Chinese traditional culture; therefore, the aforementioned debate about rural clans and modernization actually still involves the opposition of two basic propositions, namely how to properly handle the relationship between the state and society and the relationship between traditional civilization and modern civilization in the process of China’s modernization. The former manifests as the interest contradiction and coordination problem between the state’s public power organization’s regulatory authority and the autonomy of social organizations and individuals; the latter manifests as whether and to what extent traditional culture should be inherited and preserved in modern society and modern civilization and how to inherit and preserve it. Further, since clans appear in rural areas and the main members are peasants, the issue of rural clans is essentially also a peasant issue; thus, the aforementioned two issues can also be transformed into how we treat peasant culture and organizations. Answering such questions involves two basic perspectives or stances, namely, is it from the perspective of modernization looking down on peasants and rural areas? Or is it from the perspective of peasants, starting from the actual lives of peasants to address peasant and rural issues; or as Cao Jinqing says, is it from the outside looking in, from the top looking down, or from the inside looking out, from the bottom looking up [35] (p2)? From the former perspective, the tradition of peasants (including culture and organizations) is certainly more negative than positive, but from the latter perspective, a completely different conclusion is reached, revealing more positive, active significance and features that conform to the logic of social development. The difference here is merely a matter of research perspective, but further into the study of rural clans and modernization, the opposition and differences in the above views seem to have the distinction between “noble” perspectives [36] (p37) and the perspectives of the masses, reflecting that research in this field may have some deep-seated bottleneck issues.

Firstly, self-centered cultural superiority and a lack of equal awareness towards peasants. The writer believes that we have become accustomed to viewing peasants as a “selfish” backward group, peasant family economy as a backward mode of operation, and peasant organizations as backward feudal organizations, and then attributing the so-called “self-interest” and “exclusivity” traits common to all human interest groups as the “narrowness” unique to the peasant group. This mindset of viewing peasants as an other is essentially a self-centered cultural superiority discourse, which imposes a way of living and culture disconnected from peasants onto peasants, while simultaneously viewing the legitimate rights and interests of the vast majority of peasants as alien, sweeping them aside, consciously or unconsciously losing the inclusive mindset of treating others with equality. Due to the aforementioned reasons, those who deny clans say that because they cannot break through their consistently recognized framework of feudal clans, they cannot acknowledge their own recognition of the public welfare and mutual aid aspects of rural clans, nor explain the astonishing changes that have occurred in rural clans. Those who affirm clans, similarly due to the limitation of a kinship-based perspective, ultimately agree with the deniers on issues such as the “self-interest,” “exclusivity,” and “narrowness” of rural clans, thus making their interpretations and evaluations of clan positivity difficult to justify, unable to transcend the established framework of feudal clan theory. For example, Qian Hang is one of the experts who affirm many aspects of rural clans, but he is also blinded by the “kinship” aspect of clans, severing the connection between clans and peasant communities, and insists that clans, as having a “private nature” opposite to state public power, can only exist as “clubs” and cannot be organizations representing peasant interests (i.e., “organizations with explicit utilitarian purposes”), otherwise they will hinder the operation of public affairs of the state and society. One wonders whether this is to prove that as an other class of peasants, they cannot have organizations that adapt to their living environment and represent their own interests? The public representative nature of clans in peasant communities no longer exists because they do not use modern societal names?

Secondly, reviewing the academic research on rural clan issues over the past decade or more, it can be said that regardless of the attitudes of scholars and despite the differences in their views, most scholars share a common starting point or basic perspective in their research, namely, they are limited to viewing and studying rural clans from the perspective of kinship (including honorary kinship) or the combination of kinship and locality, or from the perspective of traditional ethnic groups. Therefore, although this research mode has also been continuously innovated, it is still more or less as Mr. Fei Xiaotong pointed out, only seeing the “social structure” without seeing the people [37] (p374), focusing too much on “synchronic” research at the expense of “diachronic” research. This approach tends to look backwards, using a “static view” [36] (p3) [38] (p361) to study social development issues, thus causing the research on rural social structures to sever the relationship between rural clans and the main members of actual communities, namely peasants, failing to see the real significance of clan organizations for the vast majority of peasants, nor the impact of the living environments of the vast majority of peasants and their conceptual changes on clan organization choices, thereby lacking the explanatory power for reality, such as failing to explain the tremendous changes that have occurred in rural clans, nor explaining why peasants show great enthusiasm for participating in clan activities. Because of the inability to explain these issues, it is also impossible to logically and convincingly explain the many differences in research. Academic research naturally involves disagreements, but when disagreements are too significant or some basic issues are difficult to reach a consensus, it indicates that existing research is not mature enough or lacks academically powerful explanatory results. Therefore, if rural clan research wishes to delve deeper and achieve breakthroughs, the writer believes that it is necessary to discard the self-centered cultural superiority characteristic of noble thinking, overcome the static thinking habits of “feudal clan theory” and the backward political consciousness of peasants, and face the diverse choices of living ways and social interests in urban and rural societies; overcome the single structural view, closely connect the research on rural clans with their interest subjects, peasants, rather than severing the relationship between clans and peasants, thus overcoming the static view of rural clan issues.

参考文献:

[1]王沪宁。当代中国村落家族文化——对中国社会现代化的一项探索[M].上海:上海人民出版社,1991.

[2]钱杭,谢维扬。传统与转型:江西泰和农村宗族形态[M].上海:上海社会科学院出版社,1995.

[3]王铭铭。村落视野中的文化与权力——闽台三村五论[M].北京:生活。读书。新知三联书店,1997.

[4]朱虹。乡村宗族文化兴起的社会学分析[J].学海,2001,(5)。

[5]买文兰。中国农村家族势力复兴的原因探析[J].华北水利水电学院学报,2001,(3)。

[6]余红。中国农村宗族势力为什么能够复活[J].南昌大学学报,1996,(3)。

[7]费成康。中国的家法族规[M].上海:上海社会科学院出版社,1998.

[8]王朔柏,陈意新。从血缘群到公民化:共和国时代安徽农村宗族变迁研究[J].中国社会科学,2004,(1)。

[9]肖唐镖。宗族与村治、村选举关系研究[J].江西社会科学,2001,(9)。

[10]兰芸芝。宗族势力困扰村民自治[J].中国社会工作,1995,(5)。

[11]吴思红。村民自治与农村社会控制[J].中国农村观察。2000,(6)。

[12]袁正民。宗族势力对村民自治的影响[J].学术论坛,2000,(6)。

[13]吕红平。农村宗族问题与现代化[M].保定:河北大学出版社,2001……

[14]朱康对,黄卫堂,任晓。宗族文化与村民自治——浙江省苍南县钱库镇村级民主选举调查[J].中国农村观察,2000,(4)。

[15]仝志辉。农民选举参与者的精英动员[J].中国社会科学,2002,(1)。

[16]贺雪峰,仝志辉。论村庄社会关联——兼论村庄秩序的社会基础[J].社会学研究,2002,(3)。

[17]郭正林。中国农村权力结构中的宗族因素[J].开放时代,2002,(3)。

[18]胡荣。村民委员会选举中影响村民对候选人选择的因素[J].厦门大学学报,2001,(1)。

[19]杨通红。李灿荣。民营企业:何时对家族经营说不[J].行为科学,2000,(3)。

[20]汤美芳。私营企业从家族式管理走向现代化管理的制度障碍[J].资料通讯,2001,(12)。

[21]储小平。家族企业是一种低效率的企业组织吗?[J].开放导报,2000,(6)。

[22]潘必胜。乡镇企业中的家族经营问题——兼论家族企业在中国的命运[J].中国农村观察,1998,(1)

[23]陈躬林。家族企业:有待于正确评价的企业制度[J].东南学术,2002,(1)。

[24]李成贵。当代中国农村宗族问题研究[J].管理科学,1994,(5)。

[25]黄世楚。宗族现代化初探[J].社会学研究,2000,(4)。

[26]周殿昆。中国农村家族信用复兴及企业发育问题分析[J].改革,2002,(6)。

[27]赖扬恩。传统宗族社会结构与农村工业化道路抉择[J].东南学术,2002,(4)。

[28]嵇平平。村落家族文化对人口素质的影响——对河北省西村的社会调查分析[J].中国人口科学,1998,(1)。

[29]何清涟。当代中国农村宗法组织的复兴[J].香港:二十一世纪,1993,(4)。

[30]谢维扬。农村宗族活动有利于中国现代化吗[J].探索与争鸣,1995,(8)。

[31]钱杭。论汉人宗族的内源性根据[J].史林,1995,(3)。

[32]杨平。湛江农村家族宗法制度调查[J].战略与管理,1994,(1)。

[33]秦晖,苏文。田园诗与狂想曲——关中模式与前近代社会的再认识[M].北京:中央编译出版社,1996.

[34]陆学艺。内发的村庄[M].北京:社会科学文献出版社,2001.

[35]曹锦清。黄河边的中国[M].上海:上海文艺出版社,2000.

[36]温锐。理想。历史。现实:毛泽东与中国农村经济变革研究[M].太原:山西高校联合出版社,1995.

[37]费孝通。个人。群体。社会——一生学术历程的思考[A].乡土中国生育制度[M].北京:北京大学出版社,1998.

[38]温锐。游海华。劳动力的流动与农村社会变迁:20世纪赣闽粤三边地区实证研究[M].北京:中国社会科学出版社,2001.